The Splendour Returns

by Dr John Wells, Auckland City Organist 1998 - 2012

Originally published in the Auckland Town Hall Organ Inaugural Programme, 2010.

The original organ in Auckland Town Hall was installed in 1911 – a new organ for a new Hall. This organ was rebuilt in 1970, so comprehensively that a second organ was created. The team who were advocating a second rebuilding obviously would have a credibility problem from the outset. To say that the 1970 project failed because the organ wasn't loud enough – true though that was – seemed rather unsophisticated. That argument wasn't completely convincing and there were indeed other reasons driving our new project. The sort of tone the 1970 organ produced was gradually seen (or heard) to be deficient and there were increasing issues with the deterioration of some components. Nevertheless, the argument ran, if the first rebuild was a failure, what guarantee was there that the second rebuild would be any better? To understand how that issue was overcome requires a little explanation.

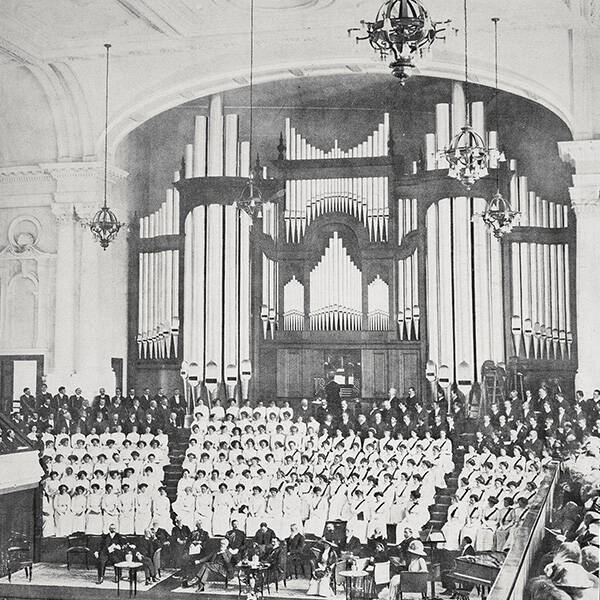

The 1911 organ was built in a style variously called romantic, orchestral, Edwardian or even English Town Hall. Such organs had a rich, colourful palette of sounds with plenty of punch in the lower and middle registers. They had been built in Europe from around the middle of the 19th century and they benefitted from a number of technical innovations in organ action and winding. The new possibilities, over roughly half a century or more, had often resulted in hypertrophy – enormous organs with up to seven manuals and occasionally even double pedalboards. Mechanical infatuations had run ahead of musical considerations: the tail was wagging the dog. Such organs were far larger than would ever be needed to play the repertory from a purely musical point of view. The caricature of the organist as megalomaniac owes a lot to this period.

In the early 20th century a reaction set in. Fuelled partly by economics and partly by a genuine aesthetic revulsion at the sounds of and performances on these monstrous machines, the 'Bach' organ was promoted as a cure-all to many perceived ills. Such a baroque style had a lighter, more transparent sound, with more upperwork and a lighter foundation tone. This style of design also required a positioning of the instrument which was not available in our particular Town Hall, but this point was brushed aside. Many romantic organs were rebuilt on the principle that 'baroque' was better, by definition, than romantic. It was a classic case of throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

This organ reform movement reached England and North America in the 1950s, and washed our antipodean shores in the late 1960s.

It stimulated the construction of some small but fine instruments here – lean and mean, if you like, and well suited to certain styles of music. But a number of fine romantic instruments were ruined or, at best, seriously compromised – here in New Zealand and most certainly elsewhere, too. Our own Town Hall organ was replaced with virtually a completely new instrument behind the beautiful old façade.

The nub of our situation, which was not unique, was that a romantic instrument best suited our Hall's needs. Why? Because of the acoustical characteristics of the Hall and its organ chamber and, pre-eminently, because of the kind of functions for which the organ would be used. These had to include accompanying or playing with choirs, bands and orchestras in a variety of musical styles; and it was precisely there that the miscalculations of the 1970 planners first began to be apparent. The justification for the second rebuild, then, was that – partly with the wisdom of hindsight and partly with a much greater appreciation internationally for romantic organs as well as baroque (or 'classical') instruments – we could proceed with confidence that the second rebuild would indeed better suit the needs of the Hall by remembering what these were, rather than by building in any style that happened to be fashionable. We could then say, with some credibility, that the first rebuild was a mistake that could be rectified. There was nothing wrong with a classical organ; it just was not, and never could have been, the right choice for our Hall.

The thought behind the project had to be ambitious enough to consider building an almost completely new organ, because that was what was done in 1970; it was never conceived as a restoration, renovation or improvement. You are listening to the third organ built in this Hall. The project never was, and never could have been, a one-man show, either. In the very early stages, three professional organists (Robert Ampt, City Organist of Sydney; Martin Setchell, City Organist of Christchurch; and David Rumsey, then of the Sydney Conservatorium) joined the City Organist in assessing and reporting on the organ sound. There was unanimous agreement that the intensity of tone did not even "drive the room" properly, let alone accompany a full orchestra. The volume fell off markedly about halfway down the Hall. Upon that crucial report the new project was largely built, with a call to restore the "spirit, power and quality" of the original 1911 instrument without requiring a literal reconstruction, as is sometimes done. This course was seen to be – and has indeed proven to be – far more exciting.

As you can see, the organ retains the original 1911 show-pipes, now beautifully cleaned with re-oiled oak casework. This lovely design is rightly protected as a heritage item. The console is new but built on the same lines as the original and located back in its original position within the organ case. Very fortunately, some 1911 pipes have survived all the changing fortunes of the instrument; most of these have been lovingly and skilfully repaired and revoiced, and (re)incorporated into the instrument. Along with the Māori ranks, they are very special to us and, as is quite fitting, they make a historical statement without in any way undermining the musical and traditional integrity of the instrument as a whole.

Two of the stops have been designed to capture the spirit of two traditional Māori instruments – the pūkāea and the kōauau: 61 Pūkāea pipes and 61 Kōauau pipes have been made, with Māori decorations on the largest (= lowest) 12 pipes of each rank; we believe the carvings are unique, as are the glass pipes of the Kōauau. The idea of making imitative ranks is not new in the broad history of the organ: many traditional organ stops are imitative, not in the sense of producing something less than the original, but very much in the sense of producing a new and fascinating sound to add to the traditional palette of colours available to the performer.

We were able to propose and implement two more ideas. One is an internal viewers' walkway inside the organ; the Māori carvings are among the myriad interesting features visible from this passage. The second is a model organ with three stops and five keys which is permanently on display in the Town Hall. It is supposed to be child-proof and has already been christened at an Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra Open Day; the ingenuity of young New Zealand brains necessitated just one repair and one design modification. Now, we hope, it really is child-proof!

I have already been asked "is this a New Zealand organ?"

No, it is not, in the sense that there is no such thing as 7 'New Zealand piano' or a 'New Zealand violin'. It is an organ in the full traditional and international sense. But it does contain unique features and two of those are the Māori stops. Otherwise, the stop names follow the normal style for an English Romantic organ. Overarching all of these considerations is the desire to make this instrument truly an organ for all New Zealand music lovers, Aucklanders and visitors alike.

The future uses for the magnificent Town Hall organ remain much as before: solo organ concerts; concerts with orchestras and choirs; graduations, civic ceremonies and other corporate functions; recordings and broadcasts. But the way the organ programme is planned to develop is not "much as before". Now that we have an instrument which can hold its head up in the company of any other organ in the world, a programme of concerts by national and international artists can begin which will add a new facet to the fine music concerts that our city already offers. Now we have an end to conductors looking up at the organist, like Oliver Twist, and asking for more. Now we have an organ with a 'wow factor' that will impress even the most casual listener. May this instrument, in the hands of skilful musicians, open the door to the great world of organ music that lies behind, waiting to be enjoyed but having been under-appreciated here for so long.

The Splendour Returns

by Dr John Wells, Auckland City Organist 1998 - 2012

Read more

Orgelbau Klais of Bonn

Builders of the Auckland Town Hall Organ

Read more

2010 Klais Specification

Stops List of the Auckland Town Hall Organ

Read more

All Works Performed

2010 - 2024

Read more

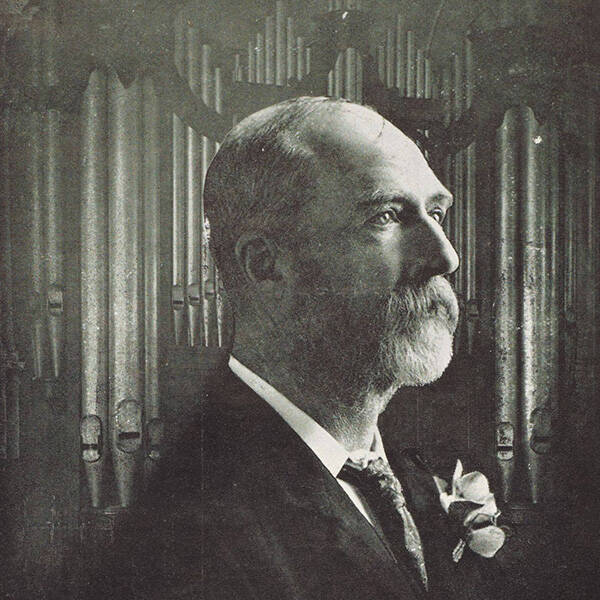

Sir Henry Brett's Gift to the City

Read more

1911 Norman & Beard

Read more

1970 Croft & Son

Read more

2010 Klais